Maturity and Quality

Nuts. Hull splitting, hull separation from the shell, shell splitting, decrease in fruit removal force, drying of hull and kernel.

Dried Fruits. Fruits destined for dehydration must be harvested firm-ripe to obtain good-flavored dried fruits.

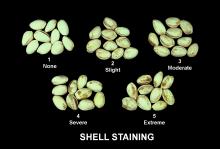

Nuts. Color; texture (crispness); flavor: development of staleness and rancidity; moisture content; incidence of decay-causing fungi; insect damage. Nuts in the shell have longer storage potential than shelled nuts. Broken pieces are more perishable than halves or whole kernels.

Dried Fruits. Color; texture (chewiness); flavor (sweetness, acidity, sulfur residue, off flavors); moisture content; incidence of decay-causing pathogens; insect damage. The lower the moisture content the longer the postharvest-life.

Postharvest Handling and Storage

0-10°C (32-50°F)

The lower the temperature the longer the storage life. Some products can be stored frozen at -18°C (0°F) for a year or longer and remain in good condition.

Very low [>1 ml/kg·hr at 10°C (50°F)] due to the reduced water content of the products and the effects of heat on the living status of the tissues.

To calculate heat production, multiply ml CO2/kg·hr by 440 to get BTU/ton/day or by 122 to get kcal/metric ton /day.

55-70% depending on the moisture content of the products (ranging from 2 to 20%)

Equilibrium relative humidity should be identified and used to maximize storage-life. Packaging in moisture-proof containers is recommended.

Oxygen levels below 1% are very effective in delaying rancidity, staleness, and other deterioration symptoms. Either oxygen levels below 0.5% (balance nitrogen) and/ or carbon dioxide levels above 80% in air can be effective in controlling stored-product insects and may provide an alternative to chemical fumigation. Packaging using vacuum or nitrogen flushing to exclude oxygen is recommended to maintain product quality.

Disorders

Physical damage. Broken nut kernels have shorter storage-life than intact kernels. Similarly, pieces of cut fruits deteriorate more rapidly than fruit halves.

Sugaring. Some dried fruits (such as raisins, figs, prunes, dates, and persimmons) are subject to sugaring on the surface or within their flesh. Incidence and severity of sugaring increase with storage temperature and time. Sugar spotting is a crystallization of sugars under the skin and in the flesh; it may be reversed by gentle heating.

Odor transfer. Nuts (because of their high lipid content) can easily absorb odors from external sources. Thus, they should not be stored with other commodities that have strong odors.

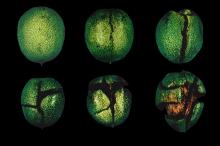

Ammonia damage. Nuts are very sensitive to ammonia damage which causes blackening of external tissues. Ammonia can also cause darkening of dried fruits.

Aspergillus flavus. Infection of nuts can begin before harvest especially under rainy and humid conditions, and when nuts have insect damage. Fungus-infected nuts are usually removed during the sorting operation to prevent aflatoxin production and contamination that could make the product unsalable since the maximum level of aflatoxin allowed is 15 parts per billion. The best way to prevent fungal growth on harvested products is to maintain the optimum range of temperature and relative humidity throughout the handling system.

Insects

Nuts and dried fruits can be damaged during storage by various stored-product insects. Infestation by insects can be minimized by the use of good sanitation, fumigation with an approved chemical fumigant, and physical protection against re-infestation. Irradiation, heat treatments, and controlled atmospheres provide additional tools for insect control. Storage below 13°C (55°F) will prevent insect feeding damage and reproduction. Storage at 5°C (41°F) or below will control insect infestation. Packaging in insect-proof containers minimizes reinfestation.